Welcome to my work of fiction: The Resurrections of Wilfrid Louie

Preface

“What purpose does memory serve if you can’t hold a grudge?”

James Randolph Beech

“Wilfrid, you must not be like him. Don’t make other people’s problems your problems. My brother thought he could give without end. But his body knew better. His body kept score.”

Yee Ah Louie

This is a work of historical fiction inspired by the life of Wee Hong Louie, my step-grandfather.

Although some of the characters are real – in this telling they’re creations of my imagination.

So, it’s safest to say: I made it all up.

It’s the story of two families whose journeys intertwine: The Beech family and the Louie family.

My Step-Grandfather, Wee Hong Louie

Chapter 1 - Remembering

October 1966• Algonquin Park, Ontario,Canada

“Common Loons… have four distinct calls. These are the tremolo, wail, yodel, and hoot. The tremolo sounds like a crazy laugh and is used… to signal alarm or worry... The wail is one of the loveliest of loon calls. It is used frequently during social interactions between loons and… to regain contact with a mate during night chorusing... The yodel… is a long, rising call with repetitive notes in the middle and can last up to six seconds. It is used by the male to defend territory... The hoot is a one-note call that sounds more like hoo. It is mainly used by family members to locate each other and check on their well-being.”

Hinterland Who’s Who, The Common Loon

An autumn sunrise slowly burns the mist off the surface of Whitefish Lake. Wilfrid Louie stands on his dock. He looks around the landing that bears his name and across the bay at a bridge that spans the narrows.

The railway bridge was built by lumber baron James Randolph Beech (JRB) when he negotiated a red pine timber license in Algonquin Park. Shipping by rail reduced the time and cost of driving the logs down the Bonnechere, Madawaska and Petawawa Rivers.

Wilfrid Louie places an envelope marked “Miriam” on the fish-cleaning table that sits on the dock. There, she is sure to find it. He places a multi-pocketed khaki hunting vest on the middle bench of the boat.

At sixty-nine years, and despite a gloomy prognosis, and increasingly foggy mind, Wilfrid Louie can gingerly step down into the aluminum fishing boat and crank the nine-horsepower motor.

The outboard coughs small puffs of blue in low tones as the boat splits the still water and nudges the remaining mist to either side. Wilfrid Louie takes a deep, deliberate breath.

A loon calls out from the far end of the lake in search of its mate. An ancient creature, the loon is the waterfowl that time forgot – a wiry and greasy bird whose dense bones allow it to dive into lakes in search of perch and catfish. Those same bones are a burden in its frenetic, lengthy take-offs.

Wilfrid Louie pulls up on the sand beneath the railroad bridge. He struggles up the side of the hill dragging the hunting vest until, winded, he stands on the wide railing and looks back across the bay. He thinks to himself – how ironic to stand on this bridge constructed by the Beech family in this very moment.

Wilfrid Louie takes his time to catch his breath and gain control. Seconds and minutes pass as he strings together his life’s events in his consciousness. He struggles against his mind’s recurring tendency to wander.

He rummages through his memories as if they are endless piles of raw footage – holding strips of frames up to the light – tossing most back onto the floor – and splicing together a series of only those that best tell his story.

Wilfrid Louie wonders if the filament between his family and that of the Beech family had been destined to braid from the very start.

He remembers his father, Yee Ah Louie, and his search for fortune. He pictures his mother, Shirley, and his sister, Lilly. He thinks of his friend, David Chase. He remembers the story of a murder.

He struggles to hold the most prized, edited frames all at once within his imagination. And coming back through the haze of his mind’s eye, there is the one he does not want to fade – the one he needs to see clearly in this moment.

Miriam.

Wilfrid Louie sees her penetrative eyes, her wicked smile. He hears her crazy laugh.

Chapter 2 - The Briefing

November 1885 (81 years earlier) • Beech Company Building, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

“…the rich undergo cruel trials and bitter tragedies

of which the poor know nothing…

The poor sit snugly at home while sterling exchange

falls ten points in a day. Do they care? Not a bit…

But the rich are troubled by money all the time.”

Stephen Leacock, Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town

Francis Beech and his younger brother, Peter, climb the stairs to the third floor of the Beech building in Montreal’s financial district. Their father has summoned them to the boardroom.

“There is a silver cookie tray being passed around the parlour – and we Beeches are stuck in the bush chopping down trees, sweating our arses off,” grumbles the towering, bearded patriarch, James Randolph Beech (aka JRB).

He is seated at the head of his boardroom table in his custom-built oak and leather chair – specially adapted for his unusual height. The pendulums of the ornate case clock that stands in the corner of the room can be heard.

Francis Beech is alert as he and his brother take their seats at the table. He has learned to observe subtle hints of a shift in their father’s mood – whether the élan in the striking of a match or gloom in his tone of voice.

“There is enough economic spillage with the construction of a rail line to transform our family’s destiny,” says the lumber baron packing tobacco in his pipe. “Beyond the construction contract, the key to financial windfalls is the land adjacent to the railway that will skyrocket in value. The millions of empty acres in the bush and prairie are nearly free for the taking. Those who know the future route or, better yet, choose its path can make investments that will create trust funds for generations.

I’m frustrated at having missed out on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, but determined to play a role in the next chapters. The BC regions of the Shuswap and Okanagan represent our golden opportunity for an extension railway line.” JRB rises from his chair and slowly walks behind his sons – around the perimeter of the boardroom.

“I’ve used my connections in Ottawa and Victoria to lobby for the contract. This is our chance to join the ranks of the nation’s powerbrokers. They’ll never invite us in. We need to knock down the bloody door,” he says pointing with the tip of his pipe.

“The necessary contributions and handshakes have been made. You will travel as my representatives to the town of Barkerville, in the interior of British Columbia, for a discreet meeting with our partners to close the deal.”

Francis and Peter Beech

Although not giants like their father, the brothers are of above average height and topped with shocks of sandy blond hair. Two years separate Francis from his younger, more extroverted brother. Francis is vigilant and disciplined, Peter is fearless and driven. They have attended the best schools – standing out on both the ice rink and debating team.

“Peter knows that I’m here. That’s why he’s not afraid of being so reckless,” Francis said over breakfast to their mother, Beverly Beech, while his brother slept in. And while it would never occur to Peter Beech to study the nature of their bond, to Francis it is a topic of some importance. “Ours is a relationship of razzing camaraderie and unspoken, unshakeable loyalty,” he explained to his mother. “And our complementary skills make us a formidable duo.”

The favourite moments of their childhood occurred during summers with Beverly at the family cottage on Lake Massawippi in Quebec’s Eastern Townships.

These were long sunny days – far from scrutiny – spent reconnoitering the forest, building forts, swimming, and fishing. Beverly let them run wild but enforced the boys’ household duties.

Thanks to their mother, the boys were taught impeccable manners in the meeting and greeting of others – no matter their station – to make eye contact, and to engage in dialogue.

Preoccupied with growing his businesses, JRB did not often join his family at the cottage. On the occasions he did, he was able for the odd weekend to relax – calling his sons for supper by his affectionate nicknames: “Gem” for Francis and “Bull of the Woods” for Peter.

With the wail of loons as their background music, they took their time enjoying family dinners in August and early September on the sprawling porch that overlooked Lake Massawippi. Dessert was typically served a few minutes before the colourful spectacle of sunset.

Over dinner, much to his mother’s delight, Francis would share an insight – an interesting story he had read in the encyclopaedia from the cottage study.

“Did you know that Polar Bears are the most menacing of all bear species and can be over 10 feet tall? They sever a man’s head with one swipe,” Francis explained looking round the table to gauge his listener’s reactions. “It’s possible that members of Franklin’s expedition were devoured by these monsters.”

Peter would, by turn, talk of the boys’ adventures in the forest or on the water.

“You’re a boy of action. A Bull of the Woods!” said his father with a tousle of his son’s thick head of hair.

At the end of an evening the boys most clearly remembered, their father gifted them pocket watches that he had purchased from Henry Birks in Montreal. Each of the treasured possessions was engraved on the back with the boy’s nickname along with JRB’s family motto: Not good enough – Beeches must be better.

That night, lying in their twin beds, Francis, stared at the ceiling and reflected on the evening.

“I think Father enjoyed my story over dinner. He was looking right at me,” he said. “Don’t you think?”

“I don’t know. Maybe,” replied Peter Beech pulling his blanket over his shoulder. “I don’t get why you worry so much about what people think – even at the rink – especially what Father thinks.”

Francis Beech rolled onto his side to face his brother’s bed. “What’s wrong with worrying about people? You don’t seem to care about anything except what you’re doing in the moment. How is that any better?”

“I do too,” his brother replied. “Maybe you’re right about one thing though – I don’t care who’s watching,” he said rubbing his eyes. “And I think there’s a difference between worrying about people and worrying about what people think. One thing’s for sure, you need to stop looking up at the stands and just play the game.” Peter Beech then closed his eyes and in seconds was sound asleep.

That the boys were destined to become influencers of public discourse and leaders of their communities is widely accepted amongst their teachers and the extended family.

JRB has pondered long and hard his options for the continuance of the Beech Company. For those that are part of the Beech inner-sanctum, although nothing has ever been said by the Founder on the topic, it is speculated that Peter, despite his carelessness, has the royal jelly. In JRB’s mind, however, the question remains open. He holds out hope for a late blooming of thoughtful authority from Francis.

The briefing

The Beech Company boardroom is the envy of the city’s business leaders for its floor-to-ceiling continuous quilted grain of black maple that wraps the four walls and the intricate stained glass above portraying images of industrious French-Canadian fur traders, lumberjacks, and fishermen – although not one French-speaking employee of The Beech Company has ever been promoted above the level of logging camp foreman.

The boardroom table is a solid oak work of art of with opulent birdcage carved legs – customized to a height of 35 inches. More than one company director of shorter stature has abruptly quit the board after experiencing the humiliating sensation of peeking over the top of the Beech family dinner table.

JRB returns to his seat at the head of the table. He methodically refills, taps, and lights his pipe, speaking calmly through the haze of Cavendish tobacco. He describes the three men with whom the boys would be meeting.

“One fellow is long-time business partner and well known to the family. The other two are brothers who wield decision-making power in British Columbia.” JRB stops and scans his sons’ expressions. He embraces the moment of silence between them and watches for a squirm.

JRB lowers his voice and slows the cadence of his words.

“Don’t mess this up boys.”

“The deal is nearly set – but they’re going to squeeze us one more time… and that’s OK. If you need it to close, propose that each Coolie crew have a white manager. The payroll from these will be collected and transported monthly to Victoria.” JRB pauses and takes a long draw on his pipe.

“Whatever you do – don’t rub their noses in it – don’t remind them that they’re harlots – maintain the façade. You know and they know what this is – there is nothing to be gained by speaking the words.”

“I’m confused,” Francis says. “I thought Chinese coolie railway crews didn’t need managers. Don’t they even have their own cooks and bookkeepers?”

“That’s right. They don’t need managers, so they’ll have them in name only. At three dollars a day per manager and three Coolie crews, there should be enough sweetener to satisfy our partners,” replies his father.

It’s not lost on Francis Beech that this move represents a change for how the family sees itself. They tell each other their success has been built upon the sweat off their brows, shrewd negotiations and, indeed, some good fortune.

“Is there a risk, Father?” Francis Beech dares to ask.

“The moral calculation comes down to the simple fact that this contract will be granted one way or another by means of graft. Every other prominent Canadian family has done it – and continues to do it.” JRB holds the tip of his pipe in his clenched teeth. “If we are to take our rightful place – this is the next, necessary step.”

James Randolph Beech

JRB is a man of his word who concludes complex deals with a handshake and scribbled notes – known to leave money on the table or even modestly overpay for an acquisition. Far from being gullible or naïve, JRB knows that future partners will consult previous ones and, in a competitive market, he wants to be perceived as the most trusted of dealmakers.

The Beech Company is one of Canada’s largest lumber operations – a modern, integrated organization from harvesting to sawmills whose timber was used to construct Canada’s parliament buildings.

Constantly seeking means to increase efficiencies, JRB has constructed a railway line from Ottawa – through Algonquin Park – to Parry Sound on Georgian Bay to reduce the cost of moving timber from remote tracts.

Family members insist that JRB was destined to be a captain of industry. He was born on a grey, damp November 2nd, 1834 on the farmhouse kitchen table in the town of Massawippi Outlet in Quebec’s Eastern Townships.

JRB’s father inherited and operated the family farm until his boy was 8 years old. It was then he built Massawippi Outlet’s first general store.

And it was in this store that JRB applied the lessons on business that would guide his future success – even as a boy he had an unparalleled work ethic and an uncanny capacity for detail.

His father counted the days receipts each evening, separating the coins into piles on the pine counter. His comments to JRB as the boy tirelessly mopped, dusted and rearranged products were on the day’s revenues. “Four dollars and seventy-two cents, not too shabby,” he would say to his son. JRB didn’t see it that way. Not in the least.

Numbers were to JRB what musical notes were to Mozart. He acquired a large leather-bound ledger that he brought home at night to record and study transactions.

By candlelight in his corner of the house, JRB taught himself about credits, debits, revenue, expense, overhead and margin, factors his father didn’t consider. During the day, he experimented with the placement of products on the counter or at eye-level on the rows of shelves. He handcrafted cards in different coloured inks to describe product benefits and discounts and fixed them to the racking.

His father gave JRB ample leeway and soon found himself taking instructions from his son. “You’re too easily satisfied, Dad. You’re not a fighter,” JRB told him.

Products with the highest margins and those that represented impulse purchases became his focus. If a shop in another town were closing, JRB would swoop in and purchase the entire inventory for pennies on the dollar. In time, he developed a discipline of incremental increases in volume and profit that were the envy of shopkeepers across the townships.

Word got around and discreet information-gathering visits from competitors became commonplace. The province’s merchants murmured, “Who is this retail prodigy and how does he work his magic?”

But it wasn’t magic. It was a painstaking system driven by the stance he first took towards his father – who left him unimpressed – and in time he engraved upon his children.

The end of the briefing

JRB closes his ledger and makes eye contact with each of his boys. “Any questions?” he asks.

They shake their heads. JRB rises and as he exits the boardroom stops and turns to face his sons: “Now, go close the deal. Come home promptly, there’ll be work to do. And remember, Not good enough – Beeches must be better.”

Little did he know only one son would return.

Chapter 3 - The Bucket of Blood

November 7, 1885 • Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada

The music almost died away ... then it burst like a pent-up flood;

And it seemed to say, "Repay, repay," and my eyes were blind with blood.

The thought came back of an ancient wrong, and it stung like a frozen lash,

And the lust awoke to kill, to kill ... then the music stopped with a crash…

Robert Service, The Shooting of Dan McGrew

Francis and Peter Beech depart the head office boardroom, head home to pack, and make their way to Montreal’s Windsor Station. They take the train to Weston Station in Toronto where they catch their connection to Owen Sound – a further eight hours through tiny hamlets and empty bush.

With the trans-Canada CPR not yet complete, the options for travelling west from Ontario are to either pass through the US or embark on a Great Lake steamer at the port of Owen Sound. From there, passengers cruise through Lake Huron on their way to Fort William at the western end of Lake Superior.

The brothers are booked for one night in Owen Sound at The Bucket of Blood. They have first class tickets the following day for the season’s final voyage on the SS Algoma.

Known as the “Chicago of The North,” Owen Sound is a town on the shores of Georgian Bay, 130 miles northwest of Toronto. The Beech brothers are wide-eyed as they walk from the train station towards the intersection called “Damnation Corners” – so named thanks to the location of four taverns - the jewel of these being The Bucket of Blood.

One block to the west, the boys pass the four churches of “Salvation Corners” – home to shady priests, judgemental preachers, vindictive nuns and the dour Women’s Temperance Union whose ill-fated mission is to eradicate the evils of alcohol.

The most futile effort of local prohibition advocates is next door: Seldon House. The desk clerk of this alternative hotel that offers patrons a dry option welcomes any ray of sunshine as it tends to awaken the dormant flies upon the sills, and provide a moment of distraction from the insufferable solitude.

As the Beech brothers arrive at Damnation Corners, they hear a cacophony of music, shouting, and screams emanating from the establishments.

“My God, will you listen to that?” grumbles Francis Beech to his brother. He breathes deeply through his nose. “And the town reeks of tobacco, spilled beer, and stale urine.”

A man staggers down the street towards them shouting angrily. Apparently, he is still participating in an unintelligible dispute with those that have just had him evicted. “What you lookin’ at?” he slurs as the brothers give him a wide berth.

Peter Beech points out a woman displaying frenzied dexterity in the shadows of a darkened alcove.

“What’s she up to?” asks Francis Beech.

“From the looks of it, I’d say she’s relieving some old sod of a sperm retention headache.”

The brothers enter The Bucket of Blood and are greeted by an earnest boy who leads them to a corner booth in the dining area and offers to take their bags to their rooms. They each order the house specialty of pig knuckle – on a bed of sauerkraut with mashed potato.

The Bucket of Blood has walls of twelve-inch pine and oak floors covered in sawdust. About 50 patrons can squeeze into the dimly lit dining area. In the corner of the tavern sits an upright Heintzman piano – one of the first ever crafted in the colonies. The piano is part of the owner’s lucky winnings in an arm wrestling competition along with the services for one calendar year of Tom, the lad who greeted the brothers and can be observed rushing to and fro around The Bucket.

Since leaving Montreal, the brothers have spent their time hashing out their mission and exchanging stories of sport, women, food and drink. Today is no exception. They travel well together – relying on Francis’ discipline for organizing and Peter’s charm for introductions and negotiations. They are, with rare exceptions, considerate and cordial travellers – lessons learned from the earliest age from their mother and reinforced by their father who has zero tolerance for public displays of boorishness.

Seated at a table adjacent to the brothers’ booth are an animated, rotund couple and a dashing young man. The three quaff pints of beer, energetically debate, and share a basket of deep-fried summer sausage with a saucer of homemade German mustard (which extravagance costs them an extra penny).

Lubricated by the ale – they soon catch the attention of Peter and Francis Beech and strike up a conversation.

“Hello!” exclaims the rounder of the two men. “Won’t you join us?”

It is clear from the Beech brothers’ dress and demeanour that they are people of means.

“Thank you very much,” replies Francis Beech. “We would not wish to intrude.”

“Nonsense!” replies the man. “But I understand. Since you are not intruders, we shall have to do the intruding!”

And with that, the couple and their handsome companion slide in beside their neighbours.

Peter Beech winks at his brother and tilts his head as if to say, ‘here goes nothing.’

Francis Beech squints and leans forward. He remarks that both men, oddly, have near perfect sets of teeth.

The stout pair introduces themselves as Edmund and Ruth FitzGerald originally from Antigonish, Nova Scotia but for the past five years, proud citizens of Owen Sound. Edmund is Owner/Publisher of The Owen Sound Times newspaper and he introduces Ruth FitzGerald as his wife and secretary.

The dashing young man shakes hands with the brothers. “Lewis Tichborne,” he says. “Entrepreneur dedicated to those afflicted with miserable mastication… and also advertising sales manager for the Owen Sound Times.” He points to his shining smile and that of Edmund FitzGerald as evidence of his handiwork.

Edmund FitzGerald orders another round for the table. The boy Tom runs over two pitchers of ale.

“Newspapers?” remarks Peter Beech, “Is there money to be made in that business? Seems there’s an awful lot of competition. Back home in Montreal there’s a new one launching and another one closing every few months.”

“They are the lifeblood. Newspapers are the future!” exclaims Edmund.

The Beech brothers are expressionless.

Edmund tries again. “Newspapers weave together the fabric of our communities. They play a crucial role in our democratic lives,” he says with enthusiasm and some spittle. Edmund can tell the Beech brothers remain unimpressed. He leans back, rolls his shoulders, and gives a quick glance to his wife.

Ruth clears her throat.

“My husband’s into highfaluting publisher babble. But from a business perspective, whoever owns the printing press and the means of distribution owns the market,” she explains. “You may have too much printing capacity in Montreal. We’ve got a high-speed Gordon Printing Press – made in New Jersey – it’s the only one in Owen Sound – and it’s gonna’ remain the only one in all of Grey County, if I have anything to say about it.”

Francis Beech sits back to think – as is his habit – and pats down the thick cowlick that sprouts above his brow. Peter Beech leans in to engage.

As does Ruth FitzGerald. “We’re now making more money from advertising than from single copy sales,” she says. “Advertising is the key. Think about it. We are the only means for merchants to get messages in front of customers in a timely manner. And when one merchant starts advertising, his competitors have no choice but to follow. If we could fit more ads in our paper – if we could print more pages – we could increase revenue tomorrow morning.”

Edmund interrupts to point out that Lewis Tichborne is his newest employee, responsible for advertising sales. “He’s breaking records every month.”

“By how much?” Peter Beech bluntly asks.

Again, Edmund FitzGerald pauses and looks to Ruth for the answer.

“We’ve put him on a commission – that’s helped keep him focused. He’s now selling for more than five hundred dollars a month,” she replies.

The handsome young man, Lewis Tichborne, smiles and winks at the brothers. He has been sitting back and paying attention – observing body language. He excuses himself from the booth and looks to the boy, Tom, for directions to the lavatory.

“But what are the paper’s politics? What’s your editorial policy?” asks Francis Beech.

“We’re not really in it for the politics. Whatever’s in the best interest of Owen Sound – that’s our politics,” says Ruth FitzGerald matter-of-factly. “If we serve the community – the community will serve us.”

“This fellow – Lewis Tichborne,” Edmund says in the man’s absence, “knows everybody – he gets to town and in months, he’s best friends with the Mayor, he’s attending all these social gatherings, he’s involved in politics. I think he’s both a card-carrying Tory and a Grit too. He has this way with people. Such a clever young man.”

“Too clever by half,” adds Ruth. “We have to keep an eye on him. I admit he does serve our purposes – the money is rolling in – but there is something about him. He’s smooth and everybody seems to love him.” She shakes her head, wary. “I just don’t know how he feels about other people. As we say back home – half the lies he tells aren’t even true,” she lowers her voice as Lewis Tichborne reappears and heads towards the table. He slows down to smile at a woman crossing the dining room.

The handsome man retakes his seat still looking in the direction of the woman and Peter Beech invites Lewis Tichborne to explain his success.

“What’s that? My success? Well you know, folks love a great smile,” he says – again flashing his flawless (if slightly oversized) choppers. Francis Beech remarks that they oddly resemble rows of unmarked playing dice.

“Let me assure you, they are as authentic as they come – fastened in a base of pink Indian rubber.”

Peter Beech presses the young man for more and motions to the boy to bring another round.

“Look, I just try to get in the head of my customer. I watch the way he moves and listen to the way he talks. What is he thinking? Who are his competitors? What’s his wife nagging to him about? Those things tell me a lot about what he fears and what he wants in life,” says Lewis Tichborne as the playful becomes serious. He picks up a pitcher and fills the glasses of his companions. “I’m never selling advertising, gentlemen. I’m pouring my customers a shot of elixir – specially concocted to treat their innermost ailments.”

The group orders more deep-fried sausage and rounds of ale that the boy Tom promptly serves. Peter Beech tells a joke. When pressed, Francis Beech explains that he and his brother are traveling west on a Beech Company project. He remains vague on details.

“Well isn’t that grand!” exclaims Edmund FitzGerald. “We’re joining you tomorrow aboard the SS Algoma. We’ve got meetings with the owners of the newspapers in Fort William and Port Arthur. What do we call them meetings, Ruthy?”

“Exploratory discussions,” she replies with a grin.

“Here’s to exploratory discussions!” toasts Edmund FitzGerald.

The table raises their glasses and clinks all around.

Ruth FitzGerald downs her pint before the men and pounds the empty glass on the table.

“That’s impressive,” says Francis.

“I come from a family of farmers and soldiers – seven older brothers. You can’t run with the big dogs if you piss like a puppy,” she says to the amusement of the Beech brothers.

“If there’s one thing Ruth doesn’t do, it’s piss like a puppy,” says Edmund squinting at the Beech brothers. “You know I saved her from a rough and tumble upbringing.”

“Thanks Honey,” replies Ruth wiping the beer from her chin. “But did you ever think it might be my rough and tumble upbringing that saved you?”

As the evening goes on, The Bucket of Blood becomes a whirling carnival of booze, music and sloppy humanity. Boundaries and inhibitions evaporate as folks spend their last dollars buying rounds for people they’ve only just met. Buttocks are grasped and necks are clammily bit in the haze of festivities.

“On with the dance, let joy be unconfined!” cries Edmund FitzGerald who now sits before the Heintzman piano and regales the room.

Appreciative patrons purchase a line of pints and shots that balance atop his instrument. A group of chambermaids and kitchen help circle Edmund in admiration – singing along anytime they recognize a tune or catch on to a chorus. His head gyrates and his mouth contorts like a howling Bassett Hound as he belts out the lyrics. He’s a sight to behold, with synchronized kicks of the piano frame the driving bass of Edmund’s high-energy Nova Scotia folk songs.

Young Tom gets up and accompanies him on the violin. The boy’s improvised solos solicit enthusiastic rounds of applause.

Back in the booth Ruth FitzGerald notices the eye contact between Edmund and a singing, sultry chambermaid while Lewis Tichborne and the Beech brothers laugh, order more rounds and sing along.

Out of the blue, Lewis Tichborne turns and asks the brothers, “Who do you think is the toughest fucker in this room?”

Despite his pickled state, and instantly suspicious, Francis Beech replies, “What do you mean? What have you got in mind?”

Truth be told, The Bucket of Blood is home to its fair share of tough fuckers.

One is seated in the opposite corner of the room, regaling his table with the telling of stories of war and adventure. John “Daddy” Hall, dressed in a stylish, if out-dated, red woollen tunic, is the town crier and leading distributor of the Owen Sound Times newspaper.

The others at the table are fixated upon the tall, wiry man as he speaks:

“I have experienced a renaissance that disguises my advanced age. Years ago, I lost all my teeth and all my hair – but thanks to the magic of a woman from Chatsworth – they have regenerated.

Born in Windsor, I was – across the border from Detroit. My father was a Mohawk Warrior and my mother an escaped slave. As a boy, I fought in the War of 1812 with the great Tecumseh we defended Upper Canada from the American invaders.

But I was captured by the bastard Yanks and they sold me into slavery.

For ten years I served a wicked man. Below his perfect blond hair – he was a liar. All smiles and laughter – he spoke of me in front of folks as if I was family.

And one night I hear him talking to his woman saying he was selling me to a New Orleans plantation owner. Now, I never believed him when he talked of me like family – but sell me to a plantation owner?

That night I knew I must escape. I had free reign of the household, so I got a few hours head start – but the son-of-a-bitch sent bounty hunters and bloodhounds at first light. Most men wouldn’t have a chance.

I was one step ahead. Before I left, I took a Spanish onion from the pantry. As soon as I hear the dogs, I stopped and rubbed it on my feet,” recounts Daddy Hall, his foot on his knee, demonstrating the technique. “And the bloodhounds lost my scent.”

The boy Tom brings a tray of rye whisky glasses to the table. Daddy Hall flips him a penny tip and his eyes light up as he continues his story:

“I fought for the Crown against the Yankees again in 1837. Then I came here – built a home in Mudtown – and that’s when my teeth and my hair – they all fell out.” He pauses, takes a sip of whisky and continues.

“Some folks say it’s called Mudtown because when it rains, the mud flows down the cliffs. But my neighbourhood is home to escaped slaves and Jamaican immigrants. That’s why they call it Mudtown. In fact, as town crier, I’m the only Mudtowner even allowed in this hotel.

But you see these teeth – you see this glorious hair,” says Daddy Hall as he parts his lips and points to his shoulder length black curls with white streaks. “That was my woman from Chatsworth – the genuine love of my life. She rejuvenated this old man – every last part of me,” he says leaning into his audience – the light of the oil lamp casting shadows on his triangular face.

Young Tom, having put down his violin, sits on a stool beside the bar. He holds a small board in one hand and pencil in the other. Attached to the board is a piece of wallpaper torn from the vestibule of The Bucket. Glancing up every few moments at the hard-partying circle around Edmund and the piano, the boy sketches.

The hotel owner cries out, “Tom, focus boy! Get over there and collect them empty glasses and dirty plates.” Tom puts the board and pencil down on the bar and runs over.

“So, who is it?” repeats Lewis Tichborne. “Who’s the toughest fucker?”

Francis Beech crosses his arms and refuses to answer.

Peter Beech looks around the harum-scarum room. “I don’t know, I suppose it’s that tall fellow with the long hair over there,” he says pointing at Daddy Hall.

Lewis Tichborne gets up from the booth and wades his way across the room to Daddy Hall. He makes a fist, twists his torso, pulls his right arm behind his body, and blindsides the unsuspecting victim with a vicious wallop to the temple.

By the time Daddy Hall gets up, Lewis Tichborne has moved on through the crowd. Enraged and confused, Daddy Hall slugs an innocent man standing next to him.

Francis and Peter Beech cannot believe their eyes. “What. The. Hell?” says Francis Beech. Peter Beech laughs at the insanity.

A Brouhaha erupts involving nearly all present. There are no sides, just a chaotic, uncoordinated melee of drunken punching, kicking, and hair pulling. Extreme levels of intoxication save many participants from more serious injury.

During the fracas, in a drunken daze, Edmund continues to bang away at the Heintzman piano – his driving beat punctuated by his surprisingly well-timed booting of the frame as he howls The Maple Leaf Forever.

“In Days of yore,

From Britain's shore

Wolfe the dauntless hero came

And planted firm Britannia's flag

On Canada's fair domain.

Here may it wave,

Our boast, our pride

And joined in love together,

The thistle, shamrock, rose entwined,

The Maple Leaf Forever…”

Finally, the music stops, the participants stumble away or lay unconscious upon the floor, and the Beech brothers are the only witnesses alert enough to appreciate the violence and audacity of what comes next.

They are transfixed as Lewis Tichborne stands up and pulls a pair of red-handled pliers from his back pocket. No one has consumed more than him, yet Lewis Tichborne calmly and squarely walks over to the comatose Daddy Hall. He turns Hall’s face upwards, holds his jaw firmly with his left hand and proceeds to extract one-by-one the newly sprouted teeth.

He then moves on to others who are sufficiently inanimate and continues his extractions. His technique has been perfected as he deliberately straddles his victims, applies the pliers, squeezes, and then yanks with leverage.

In a matter of moments his pockets are full of enamel and The Bucket of Blood is every bit deserving of its name.

The morning after

Upon rising the next day no one recalls with clarity the hours that lead up to the previous night’s violent climax. Vague recollections of drink, song, and violence along with general soreness are evidence of the folly. For some, painful, bloody gums add to the mystery.

Neither Edmund nor Ruth FitzGerald has any memory of going to bed. They awake in their room at The Bucket naked, under a blanket with Edmund lying spread eagle on his back and Ruth on her side.

Edmund opens his eyes. It takes him a moment to remember where he is. The base of his skull throbs in pain. He puts one foot on the floor, slowly sits up and stumbles towards the bathroom. As he does so, Ruth opens her eyes and spies a magenta-coloured oblong pattern on Edmund’s left buttock. In a wave of rage she is convinced she knows what it is.

“You dirty Casanova bastard!” she cries. “You were messing around with that kitchen girl last night! And the harlot bit you right on the ass! I can see her teeth marks, you sad excuse of a man!”

Edmund is stunned. While not beyond the realm of possibilities, he truly does not recall any such activity.

“Darling, I don’t think I could have done much – look at me, I’m still drunk. I honestly don’t remember doing anything – whatever I could have done… it must have been harmless,” pleads a terrified and noxious Edmund.

Sunlight comes through the open curtains of their second-floor room. Edmund squints and thinks for a second that darkness would be much better at this moment. Ruth throws the blanket off and rises from the bed. Standing naked, she addresses her equally bare-assed husband.

“You can goddamned well go to Port Arthur on your own. Have your exploratory discussions and show them just how smart you are. Pray to God they don’t ask a single meaningful question because I won’t be there to bail you out!”

She turns to find some clothing from the previous night and she sees them. In the middle of the unmade bed, previously hidden by the blanket – and before that by Edmund’s ass – is his set of flawless dentures.

Ruth FitzGerald stops talking and begins straightening the room – her hostility continues to float nonetheless. Edmund knows enough to remain silent as he dresses and packs. They have only minutes to board the SS Algoma.

Chapter 4 - The Wreck of the SS Algoma (The Beech Brothers’ voyage to Barkerville)

November 8, 1885 • Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they called 'gitche gumee'

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomy…

Gordon Lightfoot, The Wreck of The Edmund FitzGerald

Aboard the SS Algoma

The Algoma is a game-changer.

Deemed the safest in Canada, she’s a luxurious 264-foot, modern marvel constructed in Glasgow, Scotland for The Canadian Pacific Company.

Francis and Peter Beech are duly impressed as they cross the gangway. “Isn’t she beautiful?” Peter asks.

“Anything that carries us away from this miserable backwater is beautiful in my books.”

Until the transcontinental railway is completed through the rugged Ontario bush the Algoma and her sister ships, the Alberta and Athabasca, are the means of transportation for freight and passengers from Georgian Bay to Port Arthur at the western end of Lake Superior. There, travellers connect to the railway and can head west.

Ships of this size cannot pass through the Welland Canal, so after the ocean crossing, the vessels were sliced in two at Montreal. Wooden blocks plugged the open ends and tugs pulled them through the locks and across bodies of water until they were reassembled in Buffalo. The final stages of assembly and finishing touches were performed in the shipyards of Owen Sound.

A glittering coalescence of brass, white gloves, velvet and single malts – the Algoma is a gem of refinement in the austere hinterland of Northern Ontario. There is room for 200 passengers on the opulent and spacious first-class level. Another 300 can be accommodated on the more spartan steerage level below.

In the name of safety and modernity, she is fully electrified with not a single open flame on board. Deck lighting is courtesy of large glass-covered Edison lights. Attentive porters illuminate electric lighters for the cigars and pipes of first-class smokers.

There’s no need for candles or oil lamps as cabins are equipped with electric reading lights. When the Algoma sails at night, the inhabitants of Manitoulin Island wonder whether her eerie, electrical incandescence is that of a Great Lakes ghost ship.

A steam engine driving a single propeller supplemented by two sailed masts give the Algoma outstanding speed and stability. She makes the passage from Owen Sound to Port Arthur in less than forty hours. For this, her final round trip of the season in the dicey month of November, the Algoma is far below her passenger capacity.

Edmund and a still-steaming Ruth FitzGerald join the Beech brothers and another dozen passengers in first class. Although his room is in steerage, Lewis Tichborne finds a way to mingle above as well. The now toothless Daddy Hall, a guest of the FitzGerald’s in recognition of record newspaper sales, is among the thirty-five passengers registered on the lower deck.

It’s a sunny autumn day as the ship leaves Owen Sound heading north-northwest on the still waters of Georgian Bay. Lewis Tichborne, Daddy Hall, and Edmund FitzGerald join the Beech brothers on the deck for a smoke and to admire the stark beauty of their surroundings. The sky is clear and the men hear the haunting tremolo calls of the last two loons to migrate south in the shallows off White Cloud Island.

“Turn a map of Ontario 45 degrees clockwise and the land mass bears a striking resemblance to the form of an Indian elephant,” Edmund FitzGerald explains to Peter and Francis Beech. “Essex County becomes the trunk; Niagara, the front legs; The Bruce Peninsula is the tail and our little town is tucked tightly beneath the wagger – Owen Sound is the malodorous rectum.”

The Beech brothers laugh and the others in the group, who had heard Edmund’s description many times before, nod in approval.

“That explains the stench of Damnation Corners,” says Francis Beech.

“My boys, we are leaving the aptly-named Grey County. A portion of God’s creation that – apart from an annual eight weeks of sunshine – is completely devoid of colour,” says Edmund FitzGerald. “Folks in this town have little else to do but drink, fight and fornicate – but, importantly, for those eight precious weeks they also find time to fish.”

“Then why in the world is Owen Sound home for such a glorious vessel?” asks Peter Beech. “I’m sure there were other options.”

Edmund FitzGerald clears his throat. “Owen Sound won the contract for the final fittings and maintenance of the CPR ships over them arseholes in Collingwood thanks to the sacrifice of the Owen Sound labourer who – in solidarity with shipyard owners – promised a ten percent reduction in wages. Equally important – was the plan to have workers from Mudtown perform the most hazardous tasks at half a white man’s wage,” he says with a wink directed at Daddy Hall.

A few hours into the trip, the first-class dining room is set up for afternoon tea. A remarkable string trio plays Pachelbel. Two long tables covered in linen are prepared with an impressive assortment of sandwiches, beverages, condiments, cakes and cookies. Fine china and silver complete the presentation.

Edmund FitzGerald fills his plate with sandwiches – cut in delicate triangles and crusts removed – of ham, Colman’s mustard and thinly sliced pickled cauliflower. He has a well-steeped Darjeeling tea with a spot of milk. Ruth FitzGerald prefers a cup of Earl Grey and a few shortbreads. Francis Beech chooses a cup of English breakfast, egg salad sandwiches and a handful of ginger snaps. Peter Beech, who has the heartiest appetite, piles an assortment of pretty well everything both sweet and savoury onto his lunch-sized plate.

The interloping Lewis Tichborne helps himself as well, inspecting samples, placing those of interest on his plate and returning others to their trays.

The group sits at a round table in the sparsely attended room. Francis Beech concludes the setting is entirely civilized. “I approve,” he says with a playful grin, sipping his tea. Observing the buffet, he spots a delicate hand come out from behind the table and snatch a shortbread from a silver tray.

“Good heavens! Would you look at that!” Francis Beech exclaims pointing to the fully revealed arm blindly feeling its way around the selection of goodies. Lewis Tichborne jumps up and marches to over the table to identify the culprit.

“I know you!” he cries.

The boy Tom stands up.

Peter Beech calls him over to the table. “Tom!” he hollers. “What the hell are you doing on the ship?”

The boy sheepishly approaches. “I heard you talking last night at The Bucket. It sounded like quite the adventure so I decided to see for myself.”

“Did you tell anyone? Do your parents know? Does your boss know?” asks a concerned Ruth FitzGerald.

Tom shakes his head.

“Well then you’ll be our guest,” says a smiling Peter Beech pulling up a chair and moving a plate of treats in front of the boy. “Join us for tea!”

Tom carries a sketchpad under his arm that he places beside the chair. Francis Beech takes notice of it. The boy has drawn a landscape of the arching, windswept trees of Manitoulin Island. Francis passes the drawing around the table. Shaking his head, “Is there anything this kid can’t do?”

Come evening, first-class passengers and a fair portion of the crew gather again in the dining room. The ship’s chichi chef, originally from Chalon-sur-Saône in France, has finally mastered the Algoma’s electric stoves and while his handmade menu cards read Boeuf Charolais, in actuality, he delights his guests with a dinner of Grey County beef tenderloin served rare with roasted herbed baby potatoes and a creamed horseradish sauce.

Meanwhile on the bridge, Captain Moore is pleased with the time being made. He prefers to navigate the islands of Lake Huron prior to complete darkness. The Captain has made known to the powers that be at Canadian Pacific that he finds November excursions to be foolhardy risks for limited rewards. Glancing at his slim manifest for this trip, he thinks that upon his return he will have it sent to Montreal to reinforce his point.

The skies cloud over and the seasoned mariner knows this night will provide him with little to no moonlight. Moore strolls around the perimeter of the deck to take in his observations and greet any passengers braving the cold winds.

Still sporting their white summer uniforms, the first-class waiting staff gather the dinner and dessert plates and then wheel silver carts of after-dinner drinks through the dining room. Francis and Peter Beech request a glass of port. “Just leave the bottle,” says Lewis Tichborne, winking to the waiter.

Entertaining the guests with smooth banter between each number is the leader of the string trio, a much-travelled musician from Montreal. Peter Beech approaches him and suggests he give Tom a chance to join in the performance. In a musical voyage around the world, the group delights with renditions of Vivaldi, Bach, Dvorak, and a sprinkling of Klezmer arrangements. The talented boy finds a way to contribute on each piece – transforming the group into a quartet with his lively violin.

Francis Beech is in a reflective mood as the Algoma cruises into the narrowing St. Mary’s River that connects Lakes Huron and Superior. He leans towards his brother’s ear, “Here we are, surrounded by this dense, primeval wilderness on either side. God knows what hidden beasts keep an eye on us or what lurks behind the first few feet of bush. All the while, we are cocooned not one hundred yards away within the safety of this magnificent, modern ship. It’s a curious thing.”

Peter Beech smiles and clinks his brother’s glass of port. “You think too much – and about all the wrong things… You want to know what I’ve been pondering?”

“What’s that?” replies his brother with a smile.

“This Edmund FitzGerald fellow doesn’t impress me much – bit of a twit actually – but Ruth FitzGerald – she’s someone we need to keep our eye on. If we want to show Father that we can deliver results for the company, it’ll be by hiring super-sharp people like her.”

Francis Beech shakes his head, “A woman? Really – to do what?”

The music stops and the maestro introduces his trio and their young violinist. “Ladies and gentlemen, I want to thank our special, unexpected guest – from Owen Sound, the young stowaway, Tom Thomson.”

A last round of drinks is served. The Algoma briefly docks at Sault Sainte Marie permitting the passengers to stretch their legs before re-embarking and tucking into their cabins for the night.

Gitchi-gami

The Ojibwa call Lake Superior Gitchi-Gami, which means “great sea.” 350 miles long and 160 miles wide, it is the largest freshwater lake in the world. As the ship emerges from Whitefish Bay into Superior, the temperature drops below freezing and snow begins to fall.

A tailwind pursues the Algoma. In order to provide greater stability on the rolling waves, Captain Moore orders the sails up. The Captain has the ideal disposition for his calling and decades of experience on the water. Resolute under pressure and clear in his commands, his crewmembers never describe him as warm or friendly. But they do appreciate Captain Moore’s coolness and predictability.

The swirling snow eliminates any visibility. The view from the bridge of the ship is hypnotizing with squalls of flakes flying towards the glass. A wet-behind-the-ears seafarer may have panicked under the conditions, but Captain Moore calmly instructs his crew to measure wind speed, make the appropriate adjustments and maintain the ship’s charts accordingly.

It’s late and, despite some unease, Captain Moore retires to his cabin for some much-needed rest. His tossing and turning precedes a more pronounced rolling of the Algoma. He awakens after a short, fitful doze and returns to his command.

Through the windows of the bridge, forty-foot walls of water greet the Captain. “This November blizzard is turning into a gale, gentlemen. All hands to the pumps,” he says without a whiff of consternation. Captain Moore immediately orders the sails lowered.

Crewmembers follow his directions running off to the masts at the stern and bow. They have hardly two feet of visibility on the open deck. The waves of Superior begin to toss the Algoma as if she were a cork upon the sea. Passengers sit up in their beds, their white knuckles gripping rails, walls and each other.

Captain Moore’s normally stoic face betrays his alarm studying the charts at the helm. “Hard starboard!” he hollers hoping it is not too late to head out onto the open lake. Waves of numbing water roll over the deck and she has almost completed her turn when an unnatural squeal of twisting steel and a shuddering deceleration lacerate the Algoma.

It is a simple miscalculation. The tailwinds are stronger than the crew calculated – and the Algoma is moving two knots faster than contemplated on the charts.

Isle Royale stands in the way and the ship strikes a granite shoal.

Hysteria ensues. Desperate for reassurance, Edmund FitzGerald frantically emerges from his cabin and grabs a rushing crewmember by the collar only to be met with an expression of terror.

The Algoma stops her forward movement and is hinged upon the shoal – rising and crashing down upon the rock with each violent swell. Captain Moore knows that this cannot continue for long. He surveys the situation and judges the waves too formidable to permit the launching of lifeboats. Panicked people gather in the first-class dining room, situated towards the stern in the back third of the ship.

Water floods the fractured hull of the Algoma and she begins to bend, pressuring deck planks to splinter and snap. Francis Beech thinks the sound, as she is again lifted and dropped upon the granite, is like the cry of some prehistoric creature. The electric pulse that weaves through the ship’s decks and cabins sparks, crackles, and is finally extinguished.

Peter Beech’s eyes adjust and he runs to the Steerage level below and bangs on cabin doors. Most are empty – he enters in total darkness calling and feeling his way around the bunks. He rushes through hallways sensing each oncoming wave as it rises and braces for the inevitable collision upon the rocks. As passengers are found – mostly women and children dressed in nightgowns and pyjamas – he directs them up the stairs towards the dining room.

Francis Beech runs to assist his brother in the rescue effort and when confident that the steerage level is empty, they join the others in the first-class dining room. A shocked and shivering collection holds onto handrails and bolted-down tables. Terrified parents tightly grip their weeping children.

It is then that the bow finally brakes away from the Algoma, splitting down the middle of the huddled group of travellers and tearing apart the first-class dining room. Parents are separated from shrieking children, lovers are torn from one another and the broken-off bow is pulled towards the open lake and sucked into black, merciless Lake Superior.

The debris-strewn stern remains inclined on the shoal locked in its repetitive, rising and pounding cycle. Every few moments, a wave washes over the remaining deck – and yet another wailing passenger is carried away.

Peter Beech again rises to action. He finds a rope and together with Francis threads it through a railing on the stern. “If the rest of this ship goes down, we’re all done for. Our only hope is to ride it out,” he yells as the brothers and Captain Moore weave the rope around Ruth FitzGerald, Edmund FitzGerald, Lewis Tichborne, a dozen other crew and passengers, and the railing.

In the panic, at the other end of Algoma’s remaining shell, Daddy Hall and a group of eight other crewmembers and passengers choose a different tactic. They climb the rigging of the rear mast hoping to rise above the terrible waves.

Each party now faces the other – one tied to the railing the other clinging to the higher rigging. To climb down the mast and attempt to cross the deck to join the others on the guardrail means certain death. To untie oneself from the railing surely brings about the same destiny. Each group makes its wager. A thrashing, tragic spectacle takes place over the longest night.

As each monster wave approaches, Captain Moore focuses his eyes upon the silhouette of the men on the rigging and counts their number. After the white water engulfs them, and then washes away he performs another tally. His helplessness in the face of the scene as their number slowly dwindles is overwhelming. Unable to turn away or to provide succour, the unflappable Captain shudders in sobs.

Their muscles weakened by temperature and fatigue, the men desperately search for means to grip the slippery poles. One youthful crewmember leaves his bleeding right-hand digits wrapped in rope and tied in place while the rest of his person is sucked clean off the mast.

In time, the bull-headed Daddy Hall is alone upon the rigging. Eyes swelled and blinking, with each surfacing he looks around as if surprised that he still clings to life.

Daddy Hall wraps his raw-boned limbs around a pole and locks them in position. While above the water, he gums blasphemous accusations towards the heavens and words of encouragement to those tied to the railing.

As the eternal night ends the stern finally stops rocking and lodges itself in the crevice on a slight angle. The winds die down and heavy flakes of snow fall gently upon the survivors.

Captain Moore releases himself from the rope. Peter and Francis Beech follow suit. They search for blankets and clothing in benches and cupboards. The others untie themselves as well. Hypothermia now becomes their greatest risk. Daddy Hall descends from his perch. The survivors from the railing hug him as if he is once again a returning war hero. The air is heavy with grief. No one speaks.

Young Tom finds his violin in its case – still dry. He turns the pegs slowly and tunes each string. The boy’s purple fingers grip the instrument, his small body sways, snow gently falls and he begins to play a melancholic In The Bleak Midwinter as the first light of dawn appears.

The horizon is slowly revealed and Peter Beech cannot believe what he sees. The jagged, steep shore is like a mirage – only 50 feet from the wreckage. The water between ship and shore, however, is rolling, deep, and deadly.

Daddy Hall is equally incredulous. A strong swimmer, he has many times swum the length of Owen Sound harbour and despite or perhaps due to his exhaustion judges these 50 feet to be an inconsiderable challenge.

He suddenly dives into the water and begins to swim towards the shore. Although thoroughly soaked from his overnight ordeal, he is not prepared for the glacial temperature. His breaths are short and his normally strong stroke is clumsy as he struggles to lift his arms over his head.

As he approaches the shore, he tries to stand on the slippery rocks only to slide back down into the water. The sad sequence repeats twice more and Daddy Hall shakes and shivers. He yells slurred words back to people on the Algoma whose eyes are glued to his struggle.

His hands and forearms bleeding from the sharp rocks, Daddy Hall is finally within a few yards when a powerful wave knocks him forward and his head hits a crag. Gitchi-gami claims one more soul and his body drifts away, face down into the murkiness.

Further cries of grief rise from the survivors on the wreckage.

Moments later, fishermen appear at the shore of Isle Royale. Together with Captain Moore and Peter and Francis Beech they string a line of rope to what is left of the Algoma and ferry the remaining souls to safety on a rowboat. The fishermen bring blankets and make a fire on the shore.

Peter Beech finishes distributing the blankets and stands beside his brother before the bonfire.

“I can’t believe we made it,” says Francis Beech rubbing his hands together to generate some heat. “I was terrified with the thought of either one of us not surviving.”

“Yet here we are, Francis. And now you’ve got quite the story to tell,” Peter Beech replies.

Francis shivers in the crisp air. He looks his brother in the eye. “Peter, you don’t seem to understand. You took foolhardy risks and I can’t imagine having to close this deal on my own – let alone explaining to Father should anything happen to you.”

“No need to worry about me, Francis,” says Peter Beech with a wry grin and a slap on his brother’s back. “If that’s indeed what you’re doing.”

Algoma’s sister ship, Athabasca, later arrives and transports the survivors to Port Arthur where they are met by reporters anxious to interview the survivors.

[NEWS CLIPPING]

The Owen Sound Times

NOVEMBER GALE SINKS ALGOMA

FULL SCALE OF CATASTROPHE IS UNCLEAR

Port Arthur, Ontario, November 9th, 1885

The last voyage of the season of the Canadian Pacific Great Lakes steamer Algoma has ended in disaster.

The Algoma started her trip from Owen Sound for Port Arthur on Wednesday. Early on Thursday morning she ran into a November gale as she exited Whitefish Bay for Lake Superior.

Conflicting news, alarming and reassuring, was current yesterday as this paper went to press. Even after midnight it was said the Algoma was the safest ship in the country and that all passengers and crew survived.

Late last night a Canadian Pacific Company official, Mr. Andrew Spinnaker, announced that the Algoma had sunk after all her passengers and crew had been transferred to another vessel. Later he admitted that many lives had been lost. An unofficial source from Port Arthur stated that only 11 have been saved out of 75 to 100 persons on board. A list of the first class passengers includes the names of Owen Sound Times Publisher Mr. Edmund FitzGerald and his wife Mrs. Ruth FitzGerald.

Whatever the case may be, the sinking is likely one of the most awful in the history of Canadian navigation.

The stories of the disaster are more than usually conflicting, and it is quite impossible to reconcile the bulk of the earlier and optimistic reports with the sinister news received after midnight. There is unfortunately only too much reason to believe, however, that the latest and worse news is nearest the truth.

The main hope that remains is that the sister ships Athabasca or Alberta may have picked up more of the passengers and crew. As to this there is no news at the time of writing.

“When I first announced that the Algoma was the safest ship in Canada and virtually unsinkable, I had good reason to believe that all passengers and crew had survived the ordeal. I can no longer make this assertion,” said Mr. Spinnaker as this paper went to press.

We are of the opinion that no boats should be allowed to leave any of our Canadian ports after the 15th of October, and certainly not later than the 1st of November. The loss of life after these dates during the last decade is something terrible to contemplate.

Chapter 5 - Bloody Barkerville

December 10, 1885 • Barkerville, British Columbia, Canada

“If you’re gonna make a mistake

Don’t you make it twice

It’s cold on the shoulder

And you know we get

A little older every day”

Gordon Lightfoot, Cold On The Shoulder

The Body

Francis Beech pulls his jacket tight around his chest. There is no wind – but the air is sharp. Barkerville is most frigid on a night like this with no cloud cover. He has stepped out of the Fashion Hotel bar without his gloves, toque or winter coat and feels the cold pinch his ears.

His brother has been gone a long time – too long he thinks – but Francis Beech is in that space between sobriety and black out – drunk enough to have lost track of time – sober enough to suspect something is wrong.

The three-quarter moon shimmers upon the snow. Under other circumstances Francis Beech would have appreciated the beauty of the night.

He reaches the edge of town and spots a body awkwardly slumped over at the foot of a tree. He is difficult to recognize at first. His scalp has been cut from the back of his head – with skin still attached at the brow – and a large flap of magenta flesh hangs forward covering his face. Blood splatters, as if flung from a soaked paintbrush, cover his hands, arms and clothing.

Francis Beech picks up a stick and uses it to lift the hairy piece of flesh and skin to reveal the face. “PETER!” he screams, as he falls to his knees expulsing the word from his core. The horror of his brother’s last moments is frozen in his facial expression.

Francis Beech’s howls of anguish awaken and frighten nearby residents who spill out of their homes wearing coats over their one-piece union suit long johns. He remains kneeled – his face in his hands. Although his extremities are slowly freezing, Francis Beech no longer feels the cold.

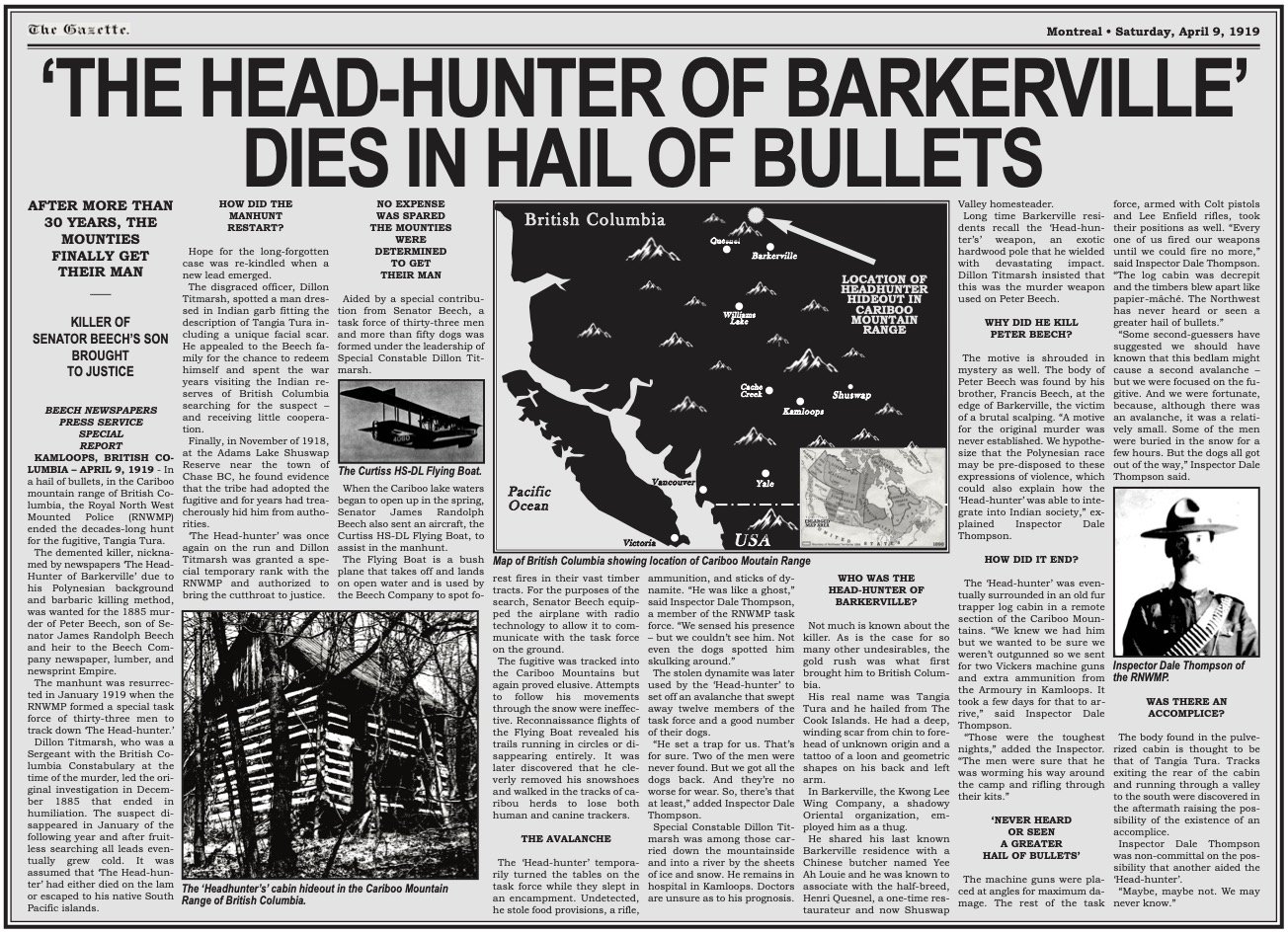

Sergeant Dillon Titmarsh of the British Columbia Constabulary is on the scene in minutes. He makes note of contusions on Peter Beech’s face and scrapes on his arms and knuckles. “Move back,” he instructs the gathering crowd as he makes sense in the shadowy moonlight of tracks in the snow surrounding the body.

“He hasn’t been gone that long,” Sergeant Titmarsh says, feeling the temperature of the skin below the collar. “We’re lucky,” he adds, peering into the bush. “Had he not been found ‘til morning, wolves would have devoured his flesh and scattered his remains.”

Barkerville

Barkerville is a gold rush town in the interior of British Columbia. As the yields of California and the Fraser Canyon shrivel, the focus of fortune-seekers has moved northeast to this secluded part of the Cariboo mountain range.

Since the arrival of the original prospectors – mostly from California – one finds Mexicans, African-Americans, Europeans and a sizable community of Chinese, who make up nearly half of Barkerville’s population of 5,000 souls.

And there is the surrounding indigenous population dominated by the Carrier Indians – their tribal name derived from the practice of mourning widows carrying the ashes of their deceased husbands.

Peace and order is expected from and enforced upon this eclectic crew. British Columbia’s political leaders in far-off Victoria know full well that a gold rush attracts the worst of humanity and they empower their constabulary and justice system to keep the town in line.

As Sergeant Titmarsh is fond of saying, “fear is the beginning of wisdom.”

The officer is a no-nonsense, reformed heavy-drinker – he awoke one morning and said “no more” (this time, really meaning it). A barrel-chested bull who stands six feet three inches tall, Sergeant Titmarsh is a veteran of the Canadian West. Ten years earlier, he was a member of Sam Steele’s North West Mounted Police contingent sent to stop American whiskey traders from crossing the border.

Sergeant Titmarsh completes his inspection, instructs onlookers to help Francis Beech to his feet and lend him a coat. He makes note of the young man’s distraught state.

“It’s my brother. His name is Peter,” sobs Francis Beech.

“You boys have any fisticuffs since you got to town? Piss anyone off?” asks Sergeant Titmarsh.

Francis Beech shakes his head.

“What brought you to Barkerville?” asks Sergeant Titmarsh.

“Uhhh, our father sent us here,” replies Francis Beech.

Within minutes, news of the atrocity spreads through the frontier town.

It is the method of mutilation, of course, that is the focus of gossip and speculation in the parlours and boarding houses of Barkerville. A mix of excitement and terror animate the discussions.

Many local residents have witnessed and heard the inhuman sounds of scalpings. They know it to be an excruciating way to die. The nest of sensitive nerves in the head make the pain unbearable and most victims pass out – bringing a ghoulish end to their blood-curdling screams.

Despite being so close to town, no one admits to Sergeant Titmarsh of hearing any such screams from Peter Beech.

The Beech brothers are recent arrivals – but everyone in Barkerville already knows their story.

The handsome duo, hailing from a prosperous eastern Canadian family, arrived with significant fanfare. Before the murder, the story of their adventure was featured in the Barkerville Nugget newspaper: “Barkerville Welcomes Heroes of Lake Superior Catastrophe”

Chapter 6 - Gam Saan (Gold Mountain)

(How Yee Ah Louie made his way to Barkerville)

December 12, 1885 (Two days after the murder) • Barkerville, British Columbia, Canada

“There are strange things done

in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold”

Robert Service, The Cremation of Sam McGee

Henri Quesnel talks to Yee Ah Louie about the murder of Peter Beech

Working alone in the back lot of the Kwong Lee Wing Butcher Shop, Yee Ah Louie clutches a rope and yanks down with his entire weight. Threaded through two sets of pulleys and tied around the right hind leg, the rope is wrapped to a post as the pig reaches a height of four feet and bleeds out. This being his third kill of the day, the blood streams down, coagulates, and fills a frontier bathtub to the brim. His raw hands and forearms have small cuts and are covered in blood.

The shop is located in Barkerville’s Chinatown at the southwest edge of the settlement and is part of an international business network that imports and distributes goods for the Chinese diaspora.

Yee Ah Louie carts his burgundy pudding to a Métis canteen owner who lives at the other end of town. The convivial Henri Quesnel, grandson of Jules-Maurice Quesnel who accompanied Simon Fraser on his explorations, mixes the viscous vat with garlic, chopped onion, and spices to create his version of boudin. When this delicacy is on the menu at Canteen Chez Henri, some regulars stay away, but his French-Canadian and European guests rave over a presentation that includes ample melted butter, Brussels spouts, and roasted crab apples.

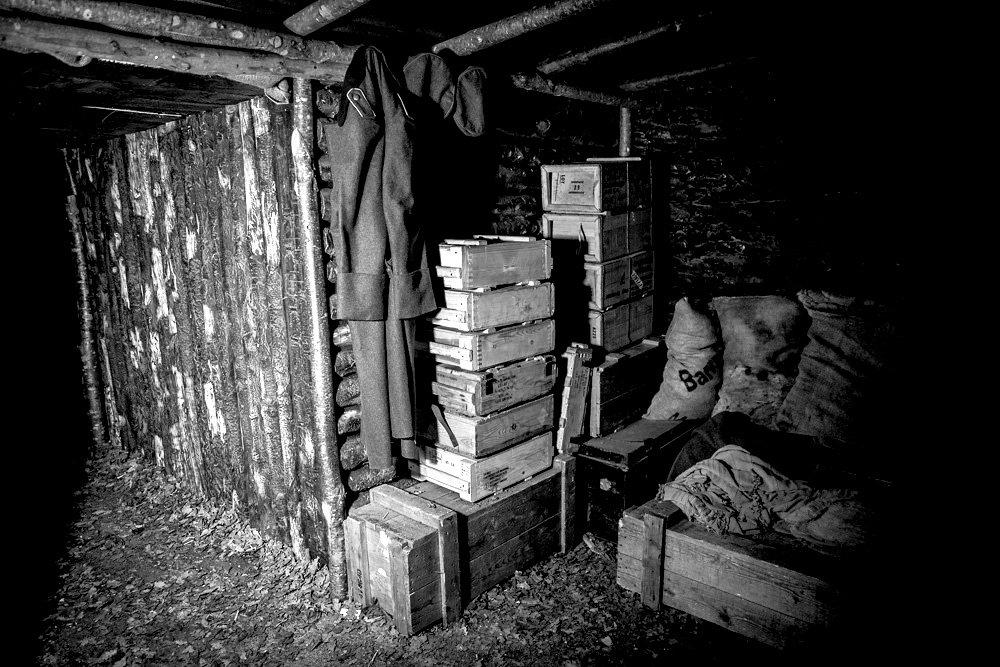

Henri Quesnel shares with Yee Ah Louie the story of the grisly discovery of Peter Beech’s body at the edge of town. Along with Tangia Tura who hails from the Cook Islands, they form a trio that has struck up a friendship founded upon common interests in good stories, good food and good drink – or any kind of drink, really – but preferably good food and absolutely good stories.

“You look like you’ve got your tongue on the ground,” he says as Yee Ah Louie pulls the heavy cart behind the canteen. Henri Quesnel has prepared a plate of Yee Ah Louie’s favourite dish – a variation on traditional Indian pemmican - Saskatoon berries mixed with venison, grainy mustard, salt, and just enough pork fat. He places his creation in the middle of the table and serves it with warm bannock bread.

Henri Quesnel pours two glasses of brandy and leans in to tell Yee Ah Louie what he has heard. Everyone knew who they were - the Beech brothers arrived in Barkerville with some fanfare. A copy of The Barkerville Nugget lies on the table with the headline: “Barkerville Welcomes Heroes of Lake Superior Catastrophe.”

“It was brutal… a vicious scalping. He must have riled someone up or maybe more than one person – but that killing - that was done by a man with rage in his heart,” says Henri Quesnel whose language, thanks to his education back east, maintains the echo of a French accent and a fair share of tournures de phrases canadiennes.

Yee Ah Louie listens while he eats, wrapping the savoury pemmican in a triangle of bannock.

“It’s a rich family. I hear his father owns all of Ottawa and half of Montreal. They’re going to find out who did it – one way or another. A little bird told me they want to build the railway into the Shuswap. Maybe someone doesn’t like the deal? Who knows, it’s a real basket of crabs. With the scalp hanging there, Sergeant Titmarsh says it might be an Indian. Me, I don’t know. Maybe yes, maybe no,” Henri Quesnel continues.

“All of Ottawa and only half of Montreal?” asks Yee Ah Louie wiping his mouth with his sleeve. “I’d take half of Barkerville, Henri. I crossed the ocean, panned mountains of dirt, had frostbite, and bloodsucking black flies but no fortune for me.”

Henri Quesnel pours more brandy. “How’s the pemmican?” he asks.

Yee Ah Louie smiles and nods in approval, washing down the remnants of a mouthful of bannock with the brandy.

“It is many years since I went to Kowloon harbour and got on a junk for Gam Saan – Gold Mountain. But those boys –” said Yee Ah Louie pointing to the Beech brothers headline in the newspaper. “Those boys were born to fortune. Still looking for mine – and pulling a cart of pig blood to Canteen Chez Henri,” he adds.

“That’s your journey – your story,” says Henri Quesnel. “You want to tell it again Yee Ah Louie? How you and Tangia Tura made your way to Barkerville?

Yee Ah Louie looks up at him. “You want to hear it?”

“Enweille, it’s a good one – and I’ve got nothing else to do,” says Henri Quesnel putting a log in the woodstove.

He fills brandy glasses again and sits down across from Yee Ah Louie.

Yee Ah Louie tells Henri Quesnel a story

“Just for you, Henri. I will tell the story again,” says Yee Ah Louie with a rare grin.

“My plan was to make my fortune and return to Hong Kong in one or two years – maybe three.

I was bornin 1842, the year of the Opium War. I lived with my mother and my dear big brother, Ah Chu – a good man. My father was not around. He worked the mines in Canton – showed up once or twice a year – sometimes with food or money – sometimes not.

Under the watchful eye of my brother, the streets of Kowloon were my home. In the market, my favourite stall belonged to an old Turk named Affendi. I think he liked me. I loved his lokum – Turkish Delight. I pinched squares when Affendi was busy and not looking. Lokum is a delicious paste of starch and sugar with pistachios and hazelnuts. Affendi added cinnamon, lemon, and orange.

I took the lokum and rolled it into a ball with my tongue to the top of my mouth and pressed it against my front teeth – to make the sweetness last.

I did it every day and a black spot grew from the sugar,” Yee Ah Louie says pointing to the hole in his front teeth. “I stopped smiling because people stared. I chewed bits of white paper – and with my tongue pushed it, like this, to hide the hole in my teeth,” he said demonstrating the technique to his friend.

“My brother, Ah Chu, was there for us. He provided for the family – working in a butcher shop. When we had a problem, we turned to Ah Chu. He fixed it. He taught me to cut meats and clean carcasses and he made good soups.

The death of Yee Ah Louie’s brother, Ah Chu Louie

When he was 20 years old – a hot and humid summer – Ah Chu, started having headaches. He said it was the air in the butcher shop. His headaches got worse and soon he could no longer see. My mother looked for help. But no one could do much.

Near the end, Ah Chu would shake. Mother was superstitious. She told me to hold his body. I don’t know if that was for him or for her. She screamed: ‘Hold him, hold him – stop the shaking!’ Henri, my jaw hurts when I remember those days,” Yee Ah Louie confesses to his friend. The eyes of both men well up.

“Father was at the doorway the next day.

He covered the window with rags and Ah Chu lay down beside him. I remember the scene clearly. He brought lamp, a pipe, a dish of black paste, a bowl, a needle, and a scraping tool.

Father placed a blanket and pillows around Ah Chu and lit the lamp. He took a small ball of the paste and with the end of the long needle, held it over the fire. It grew and turned gold. He pulled the sticky ball into strings and then rolled it and put it in the hole in the bowl.

He held the bowl above the flame and told my brother to breathe it in. I watched my father bend down and talk in my brother’s ear. My brother’s body did not shake and I swear I saw demons rise in the air.

My father was around for two days after Ah Chu died. He sold family goods of value – the ones that mother did not hide under the floorboards. Then he left and I never saw him again.” Yee Ah Louie smirks and finishes the dregs of his glass of brandy. “Another?” he asks.

Henri Quesnel pours another round.

Yee Ah Louie’s voyage across the Pacific

“That’s when I made the decision to go to Gam Saan to make my fortune. I was thirteen. I borrowed money from my uncle and told my mother I was leaving. She was a little sad – not too sad. I stole a piece of lokum to last the journey.

The morning I left Hong Kong, the sky was dark – it was monsoon season Affendi the Turk met me at the harbour and gave me a singing cicada in a bamboo cage. ‘Cicadas are a friend on a voyage. Their song is the music of your journey,’ he said. He was good to me. You know, Henri, I think Affendi knew that I stole his lokum.

The crew of junk were hard men many countries. They scared me and I stayed in my little corner below deck. After many days on the China Sea, the junk passed south of the green hills of Formosa. The sky was clear and the view was beautiful I went up and breathed in the fresh air. I was excited and I asked if we had reached Gam Saan. The crew laughed at me for the rest of the voyage.

Henri, I know you like this part. Our long trip was only getting started. After days of good wind and good weather, in no time, the sky turned black with terrible winds and rain like knives. The sails were taken down.

The floor of the ship moved up and down and I was scared. I crawled to pull myself through a hatch to see what was going on. Sailors ran around, shouted at each other in Pidgin English, and I will never forget what I saw next.

A rope broke and a sail came loose. It flapped so hard the clapping sound it made was louder than any thunder you’ve ever heard. It looked like it would snap the mast in two and smash through the deck. And that was the first time I saw him. His face had a scar from his chin to his hair,” says Yee Ah Louie drawing the path of the scar upon his own face. “He had a tattoo up his arm and on his back. He was ugly.”

Henri Quensel coughs, laughs, and coughs again. “Yes, I do like this part, Yee Ah. Continue!” he says.

“Well, the man with the scar and tattoo climbed the mast way up high with his knife in his mouth. I watched him cut the lines of the sail – one hand holding on for his life and one hand cutting the rope. Then the sail was released and it flew off into the sky like a giant bird. I could not believe his courage.

The rain and the waves did not stop and the water on the deck was up to our knees – the scar-faced man saved the junk from destruction, but I still worried we would sink.

And I was not ready to die – not then – still not today. Going down in the Pacific to be eaten by a giant squid or disappear in the mud – that’s not my way to go, Henri.

I went back to my hole under the deck and found my bamboo cage in water – no more singing for my cicada. His journey was over and I thought mine was too. I ate all the lokum and waited for the end.

And then, as fast as it came, the storm stopped and we had no more weather after that. The crew sang a song in their different languages getting the extra sail from under the deck as the sun came up and replacing the one that flew away.